Wow! What an interesting module and discussion we have been able to have this week. How collections end up at museums is something that rarely crossed my mind until arriving at the Museum of the North. I will be honest, like many museum visitors I think I was under the naive thought that museums must always have the best intentions and nothing is put in a museum unless it rightfully belongs there. Little did I know that a lot of these decisions are up to the museum policies, and can be highly debatable! There is a lot on the table to consider.

So, why do museums collect?

From my perspective, museums collect objects out of a need to keep valuable items safe so that future generations will be able to enjoy these objects for years to come. In effort to keep precious objects out of private homes/collections, museums are our society’s attempt to have a public place for these objects to be enjoyed. And we hope that curators and collections managers are keeping these items in safe, long-lasting conditions. (Marceca mentions in her video lecture that one thing that needs to be considered when bringing a new object into a collection is, can we keep this safe forever? What if there is an Earthquake? What is the building is renovated? Do we have the resources to house this object through good and bad?)

I’ve been thinking a lot this past week about who has the right to say, ‘this object can leave it’s original home and go to a museum.’ Like we discussed, there are tons of objects washed up on beaches, or found out in Alaska that should be reported to authorities so that researchers know that they exist and they can contribute to research for years to come. Other objects hold more historical or cultural significance.

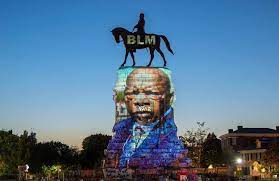

The example I brought up in our discussion on Friday was the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, Virginia. A slave owner, prominently displayed within the traffic circle at the intersection of Monument Avenue and Allen Avenue, became the epicenter of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020. The statue became the place for protesters to gather, and yoga classes and little libraries began to pop up in the area around the statue. Protest graffiti and even a projection onto the statue made it an iconic piece of protest art. The statue is owned by the City of Richmond and will be transferred to a Black History Museum

The object has become meaningful to many members of the Richmond community for a variety of reasons. And what is to be done with the statue is highly debated. The statue has to be cared for in some way, prior to the protests I am assuming that is was cared for by the City of Richmond. Now that it has more of a significant meaning to the community, the question is, who has the right to put this in their museum?

Much like Bus 142 at UAMN, a lot of people believe museums would want to have these high profile objects in order to increase visitor attendance and revues. On the other hand, a lot of the public believe that things should rightfully be cared for in museums as long as they the object has justly been given to the museum by the owner or community that it originated from.

It feels like there are a lot of things that we could analyze here, we could go down the road of talking about object’s place of origin, laws regarding ethics, museum code of ethics, and more. I will however say that after this week the biggest takeaway I have from the ethics of collections is that communities should be largely involved in decisions and discussions revolving around precious and important objects. People who have connections to objects will feel a certain way when one day they have to pay an entrance fee to go look at those objects behind glass. It’s important to work with communities related to an object to figure out the best way to care for the object and find the right home for it. Not every museum is the right place for every object. The more open and communicative museum’s are in their process of acquisitions, the more likely the object will find a safe place to be kept.

And my last thought is that museum’s truly are places where objects are kept safe. Somebody in our discussion said that they like to think of museum’s as libraries. Places where objects are kept safe so that the public can view them, learn from them, and research them. I have been so happy to hear more from various departments at UAMN and the extreme thought and care that goes into caring for the objects in the collection.

My question for the class is, what do you think is the most important part of acquisitions? We’ve learned a lot this week about different laws that govern this process, but a lot of it falls on the museum’s ethics. Any thoughts?

I agree with you and how you were mentioning some people who feel a connection to an object will feel some sort of way having to pay and go and see it on display or in an exhibit. I saw a post on one of my social media accounts mentioning how people nowadays have to pay to learn their own language if they want to, when originally it was taken away. Which is silly.

To answer your question: When acquisitioning an item, getting a valid title is important and making sure it represents the mission.

I think that one of the most important parts of acquisition would be the ethical part of it. Did the museum get the item through the right channels? Was the item ethically collected from the person before the museum?

In my mind the most important part of acquisitions is the dialog it creates within a community. If the museum simply lays claim to an object without speaking to other groups which may have claims to that object, then the purpose of the museum to serve its community isn’t being fulfilled. If on the other hand a museums approaches these groups with questions about preservation, research or contested claims of ownership, and gets these groups thinking about these issues it can improve the final outcome even if the museums itself doesn’t acquire the object, by making sure it these ideas were considered prior to determining the objects final location.

I feel that the most important part of the acquisitions process is getting the community involved. The community that it’s going to be a part of, where it came from (if not the same place), and differing perspectives about a piece are all needed. Your example of the Robert E. Lee statue is a good example – I always thought about the statue as memorializing a snapshot in history and never once thought about the slaveholder aspect of it. It took someone else’s perspective to open my eyes to that view, and it actually made me think deeper. Which is really the point of museums, isn’t it?